No products in the cart.

Techniques for Adding the Numbers 1 to 100

There’s a popular story that Gauss, mathematician extraordinaire, had a lazy teacher. The so-called educator wanted to keep the kids busy so he could take a nap; he asked the class to add the numbers 1 to 100.

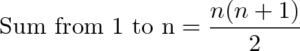

Gauss approached with his answer: 5050. So soon? The teacher suspected a cheat, but no. Manual addition was for suckers, and Gauss found a formula to sidestep the problem:

![]()

Let’s share a few explanations of this result and really understand it intuitively. For these examples we’ll add 1 to 10, and then see how it applies for 1 to 100 (or 1 to any number).

Technique 1: Pair Numbers

Pairing numbers is a common approach to this problem. Instead of writing all the numbers in a single column, let’s wrap the numbers around, like this:

1 2 3 4 5

10 9 8 7 6

An interesting pattern emerges: the sum of each column is 11. As the top row increases, the bottom row decreases, so the sum stays the same.

Because 1 is paired with 10 (our n), we can say that each column has (n+1). And how many pairs do we have? Well, we have 2 equal rows, we must have n/2 pairs.

![]()

which is the formula above.

Wait — what about an odd number of items?

Ah, I’m glad you brought it up. What if we are adding up the numbers 1 to 9? We don’t have an even number of items to pair up. Many explanations will just give the explanation above and leave it at that. I won’t.

Let’s add the numbers 1 to 9, but instead of starting from 1, let’s count from 0 instead:

0 1 2 3 4

9 8 7 6 5

By counting from 0, we get an “extra item” (10 in total) so we can have an even number of rows. However, our formula will look a bit different.

Notice that each column has a sum of n (not n+1, like before), since 0 and 9 are grouped. And instead of having exactly n items in 2 rows (for n/2 pairs total), we have n + 1 items in 2 rows (for (n + 1)/2 pairs total). If you plug these numbers in you get:

![]()

which is the same formula as before. It always bugged me that the same formula worked for both odd and even numbers – won’t you get a fraction? Yep, you get the same formula, but for different reasons.

Technique 2: Use Two Rows

The above method works, but you handle odd and even numbers differently. Isn’t there a better way? Yes.

Instead of looping the numbers around, let’s write them in two rows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Notice that we have 10 pairs, and each pair adds up to 10+1.

The total of all the numbers above is

![]()

But we only want the sum of one row, not both. So we divide the formula above by 2 and get:

Now this is cool (as cool as rows of numbers can be). It works for an odd or even number of items the same!

Technique 3: Make a Rectangle

I recently stumbled upon another explanation, a fresh approach to the old pairing explanation. Different explanations work better for different people, and I tend to like this one better.

Instead of writing out numbers, pretend we have beans. We want to add 1 bean to 2 beans to 3 beans… all the way up to 5 beans.

x

x x

x x x

x x x x

x x x x x

Sure, we could go to 10 or 100 beans, but with 5 you get the idea. How do we count the number of beans in our pyramid?

Well, the sum is clearly 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5. But let’s look at it a different way. Let’s say we mirror our pyramid (I’ll use “o” for the mirrored beans), and then topple it over:

x o x o o o o o

x x o o x x o o o o

x x x o o o => x x x o o o

x x x x o o o o x x x x o o

x x x x x o o o o o x x x x x o

Cool, huh? In case you’re wondering whether it “really” lines up, it does. Take a look at the bottom row of the regular pyramid, with 5′x (and 1 o). The next row of the pyramid has 1 less x (4 total) and 1 more o (2 total) to fill the gap. Just like the pairing, one side is increasing, and the other is decreasing.

Now for the explanation: How many beans do we have total? Well, that’s just the area of the rectangle.

We have n rows (we didn’t change the number of rows in the pyramid), and our collection is (n + 1) units wide, since 1 “o” is paired up with all the “x”s.

![]()

Notice that this time, we don’t care about n being odd or even – the total area formula works out just fine. If n is odd, we’ll have an even number of items (n+1) in each row.

But of course, we don’t want the total area (the number of x’s and o’s), we just want the number of x’s. Since we doubled the x’s to get the o’s, the x’s by themselves are just half of the total area:

![]()

And we’re back to our original formula. Again, the number of x’s in the pyramid = 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 + 5, or the sum from 1 to n.

Technique 4: Average it out

We all know that

average = sum / number of items

which we can rewrite to

sum = average * number of items

So let’s figure out the sum. If we have 100 numbers (1…100), then we clearly have 100 items. That was easy.

To get the average, notice that the numbers are all equally distributed. For every big number, there’s a small number on the other end. Let’s look at a small set:

1 2 3

The average is 2. 2 is already in the middle, and 1 and 3 “cancel out” so their average is 2.

For an even number of items

1 2 3 4

the average is between 2 and 3 – it’s 2.5. Even though we have a fractional average, this is ok — since we have an even number of items, when we multiply the average by the count that ugly fraction will disappear.

Notice in both cases, 1 is on one side of the average and N is equally far away on the other. So, we can say the average of the entire set is actually just the average of 1 and n: (1 + n)/2.

Putting this into our formula

![]()

And voila! We have a fourth way of thinking about our formula.

So why is this useful?

Three reasons:

1) Adding up numbers quickly can be useful for estimation. Notice that the formula expands to this:

Let’s say you want to add the numbers from 1 to 1000: suppose you get 1 additional visitor to your site each day – how many total visitors will you have after 1000 days? Since thousand squared = 1 million, we get million / 2 + 1000/2 = 500,500.

2) This concept of adding numbers 1 to N shows up in other places, like figuring out the probability for the birthday paradox. Having a firm grasp of this formula will help your understanding in many areas.

3) Most importantly, this example shows there are many ways to understand a formula. Maybe you like the pairing method, maybe you prefer the rectangle technique, or maybe there’s another explanation that works for you. Don’t give up when you don’t understand — try to find another explanation that works. Happy math.

By the way, there are more details about the history of this story and the technique Gauss may have used.

Variations

Instead of 1 to n, how about 5 to n?

Start with the regular formula (1 + 2 + 3 + … + n = n * (n + 1) / 2) and subtract off the part you don’t want (1 + 2 + 3 + 4 = 4 * (4 + 1) / 2 = 10).

Sum for 5 + 6 + 7 + 8 + … n = [n * (n + 1) / 2] – 10

And for any starting number a:

Sum from a to n = [n * (n + 1) / 2] – [(a – 1) * a / 2]

We want to get rid of every number from 1 up to a – 1.

How about even numbers, like 2 + 4 + 6 + 8 + … + n?

Just double the regular formula. To add evens from 2 to 50, find 1 + 2 + 3 + 4 … + 25 and double it:

Sum of 2 + 4 + 6 + … + n = 2 * (1 + 2 + 3 + … + n/2) = 2 * n/2 * (n/2 + 1) / 2 = n/2 * (n/2 + 1)

So, to get the evens from 2 to 50 you’d do 25 * (25 + 1) = 650

How about odd numbers, like 1 + 3 + 5 + 7 + … + n?

That’s the same as the even formula, except each number is 1 less than its counterpart (we have 1 instead of 2, 3 instead of 4, and so on). We get the next biggest even number (n + 1) and take off the extra (n + 1)/2 “-1″ items:

Sum of 1 + 3 + 5 + 7 + … + n = [(n + 1)/2 * ((n + 1)/2 + 1)] – [(n + 1) / 2]

To add 1 + 3 + 5 + … 13, get the next biggest even (n + 1 = 14) and do

[14/2 * (14/2 + 1)] – 7 = 7 * 8 – 7 = 56 – 7 = 49

Combinations: evens and offset

Let’s say you want the evens from 50 + 52 + 54 + 56 + … 100. Find all the evens

2 + 4 + 6 + … + 100 = 50 * 51

and subtract off the ones you don’t want

2 + 4 + 6 + … 48 = 24 * 25

So, the sum from 50 + 52 + … 100 = (50 * 51) – (24 * 25) = 1950

Phew! Hope this helps.

Ruby nerds: you can check this using

(50..100).select {|x| x % 2 == 0 }.inject(:+)

1950

Source : www.betterexplained.com